Being Hindu is the journey of a common Hindu, an attempt to understand why for so many Hindus their faith is one of the most powerful arguments for plurality, for unity in diversity and even more than the omnipresent power of God, the sublime courage and conviction of man. An extract.

For a moment, think about this. In the history of theology, one question reigns supreme amid the bloodshed – which is the one true god?

Empires rose and fell to defend the one true god, or to spread his word (you will notice that ‘one true god’-s are usually male), or to destroy the realms of the infidel or the unbeliever and cleanse places, kingdoms and nations for the rule and supremacy of the only messiah. Even today thousands of years after the last major messiahs died the bloodshed to establish the reign of the true god continues.

But what if the Hindu point of view was better understood in our world? What if the fundamental premise of Vedanta philosophy seeped in our ethics? What if the very heart of the Hindu argument was better understood?

And what is that core?

The Hindu, fundamentally, believes that there is no one true god. There is therefore no false god. Naturally if you don’t have one true god, it is tough to have a false god.

And if you don’t have a one true god or a false god, then, there are no unbelievers. For an unbeliever to exist there must be a static, defined idea of what the manifestation of the Almighty looks like – in its absence, it is very difficult to point fingers at the heretic. Without the finality of the messenger of god – and his words being the final message – how can there be an unchanging idea of the infidel?

Those then are the main questions Hinduism answers with certitude. It says that every manifestation (indeed messenger) of the Almighty has not equal validity to propagate their version of the divine truth. In a sense, the Hinduism argument is the opposite of the monotheistic faiths. It says every messenger (or prophet) is to be held true until proved false.

The Hindu path has no infidels, nor false gods. There are, it declares, as Vivekananda famously did, no sinners. In this, it takes a position diametrically opposite, for instance, to Christianity. In Hinduism, there are no souls to save. And no original sin that man is born with.

This is why Vivekananda declared at the Parliament of Religions in 1893, ‘May He who is the Brahman of the Hindus, the Ahura Mazda of the Zoroastrians, the Buddha of the Buddhists, the Jehovah of the Jews, the Father in Heaven of the Christians, give strength to you… The Christian is not to become a Hindu or a Buddhist, nor a Hindu or a Buddhist to become a Christian. But each must assimilate the spirit of the others and yet preserve his individuality and grow according to his own law of growth… The Parliament of Religions… has proved… that holiness, purity and charity are not the exclusive possessions of any church in the world…’

In fact Hinduism argues the other most audacious extreme. It says – again to quote Vivekananda – each soul is potentially divine. As always we must now ask what does that mean, how does it change my life (or yours) by the knowledge that each soul is potentially divine?

I can only explain how I have understood it and how it has worked for me. What happens is, once you start to think about this idea that each and every soul – yours included – is potentially divine you start to get a little nervous. Why? Because it takes away our emotional and psychological crutches. When you realize that in reality you have nothing to fall back upon but yourself, it breaches your most secure barriers and fortresses in the mind, the ones we usually keep protected by the idea of god.

I have always looked at the sonorous statement that each soul is potentially divine as a bit like the swimming teacher who pushes a trusting child into the deep end just at the moment when the pupil is most trying to clutch onto to her to avoid swimming himself. The teacher knows that there will be much flaying of arms, much water will be swallowed but finally the student will have to learn how to swim. The teacher is there to ensure that her ward does not drown but beyond that he is on his own.

In her now famous TEDx talk, the researcher Brene Brown explains how the word courage comes from the Latin word ‘cor’ which means heart. It comes from the ability and psychological ability to open your heart and be vulnerable.

The root of Hindu philosophy is, to me, like that. It forces you to be on your own, it pushes you down a personal path explaining that while the truth is one, every journey to reach it must be unique. The path to discover divinity inside you is a path of extreme vulnerability. It is a path fraught with accepting your deepest insecurities and facing your most frightening demons. You cannot, naturally, hope to discover your inherent divine nature until you face your most challenging anxieties.

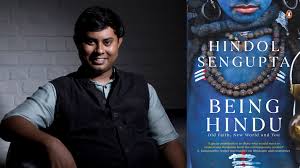

Hindol Sengupta is Editor-at-Large for Fortune India. Being Hindu is his sixth book. Published with permission from Penguin Books India.

Swarajya