The controversy about Penguin India’s decision to withdraw and pulp Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History brings to the surface issues likely to trouble scholars of India for years to come. First, the obvious: the banning of any book violates academic or intellectual freedom. Rightly so, this leads to moral indignation among the intelligentsia of India and the West. Our ancestors fought for this freedom, sometimes sacrificing their lives. Not to protect it amounts to betraying their legacy.

Yet, in this case, the rhetoric is predictable and somewhat stale:

Another bunch of Hindutva fanatics have succeeded in having a book by a respected academic banned because they feel offended by its contents. They have not understood the book, give ridiculous reasons, and threaten publisher and author with dire consequences if the book is not withdrawn. The Indian judiciary is caving in to religious fanaticism and practically abolishing freedom of speech in India.

This ready-made reaction may sound cogent but it covers up major questions: What brings Hindu organizations to filing petitions that make them the butt of ridicule and contempt? Whence the frustration among so many Indians about the way their culture is depicted? Why is this battle not fought out in the free intellectual debate so typical of India in the past?

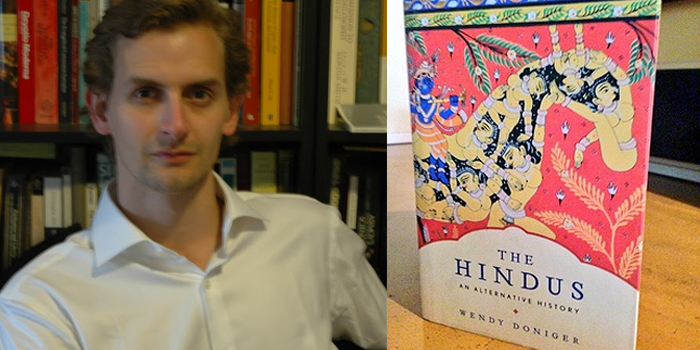

So many strands are entangled in this knotty affair that it is no longer clear what is at stake. To move ahead we first need to untangle the knot, but this requires that we take unexpected perspectives and question entrenched convictions. Drawing on the work of S.N. Balagangadhara, this piece hopes to give one such perspective. – Dr Jakob De Roover

Imagine you are born in the 1950s as a Hindu boy with intellectual inclinations. As you grow up, your mother takes you to the temple and shows you how to do puja. Your grandparents tell you stories about Bhima’s strength, Krishna’s appetite, Durvasa’s temper…. Perhaps you rejoice when Rama rescues Sita, feel afraid when Kali fights demons, or cry when Drona demands Ekalavya’s thumb as gurudakshina. Your father is indifferent to most of this stuff, but then he is very moody so you prefer to stay away from him in any case.

In school, you are taught about the history of India. You learn that Hinduism grew out of the Brahmanism imported during the Aryan invasion. The caste system is a fourfold hierarchy imposed by the Brahmin priesthood, so you are told, and untouchability is the bane of Hindu society. Caste discrimination needs to be eradicated, as Gandhi said, while the scientific temper should displace superstitious tradition, as Nehru taught.

Your teachers present this account as the truth, along with Newton’s physics and Darwin’s evolutionary theory. You feel bad about your “backward religion” and ashamed about “the massive injustice of caste.” For some time, as a student, you also mouth this story in the name of progress and social justice. Yet you feel that there is something fundamentally wrong with it. You sense that it misrepresents you and your traditions—it distorts your practices, your people, and your experience, but you don’t know what to do about it.

What is the problem? Well, the current discourse on Indian culture and society is deeply flawed, even though it dominates the educational system and the media. This story about “Hindu religion” and “the caste system” started out as an attempt by European minds to make sense of their experience of India. Missionaries, travellers, and colonial officials collected their observations; Orientalists and other scholars ordered these into a coherent image of India. In the process, they drew on a set of commonplaces widespread in European societies, which all too often reflected a Christian critique of false religion.

The resulting story transforms India into a deficient culture:

India has its dominant religion, Hinduism, created by cunning Brahmin priests; this religion sanctions social injustice in the form of a fixed caste hierarchy; instead of freedom and equality, it represents inequality and social constraint; it is basically immoral.

With some internal variation, this story is presented as a truthful description of Indian culture. Contemporary authors use different conceptual vocabularies to explain or interpret “Hinduism” and “caste,” from Marx and Freud to Foucault and Žižek. But the so-called “facts” they seek to explain are already claims of the Orientalist discourse, structured around theological ideas in secular guise. In fact, they are nothing more than reflections of how Europeans experienced India. No wonder then that the story does not make sense to those who do not share this experience.

Back to the 1970s now: you are studying hard, for your parents want you to become an engineer. Yet you are more interested in history and the social sciences. You want to make sense of your unease with the dominant story about Indian culture. So you turn to the works of eminent professors at elite universities from the Ivy League to JNU. What do you find? They repeat the same story, in a jargon that makes it even more opaque. You become more frustrated. Everywhere you turn, people just reproduce the same story about Hinduism and caste as the worst thing that ever happened to humanity: politicians, activists, teachers, professors, newspapers, television shows…. They may add some qualifications but to no avail. After spending a few years in America, you return to India, get married, and have two kids. They come home from school with questions about “the wrongs of Hinduism and the caste system.” You don’t know what to tell them. Your frustration and anger rise to boiling point. You feel betrayed by the intellectual classes.

What are the options of Indians going through similar experiences? They cannot challenge the story about Hinduism and caste intellectually for they do not possess the tools to do so. They are neither scholars nor social scientists so they cannot be expected to grasp the conceptual foundations of the dominant story, let alone develop an alternative. Maximally, they can condemn it as “racist” or “imperialist.” Even there, they are ambiguous. They feel that the West is ahead of India in so many ways. In their society, corruption is the rule and the caste system refuses to go away, but then most people around them nevertheless appear to be good men and women. How to make sense of this? There are no thinkers able to help them solve these problems.

When you turn 45, your children leave home. One fine day a colleague tells you he is with the RSS and hands you some literature. Here is an outlet for venting your anger and frustration, the rhetoric of Hindu nationalism:

“Be a patriotic Indian; the Hindu nation is great; caste is only a blot on its glory; Indian intellectuals are communists engaged in an anti-Indian conspiracy; and foreign scholars must be out to divide the country.”

This rhetoric does not give you any enlightenment or insights into your traditions; actually, it feels quite shallow. But it at least gives some relief and puts an end to the blame and insult heaped onto your traditions. With some fellow warriors you decide that the mis-education of India should stop. What is the next step?

At this point, there are ready-made traps. First, it is difficult not to notice how those in power in India decide what gets written in the textbooks. Under British rule, it was the classical Orientalist account. Mrs Gandhi allowed the Marxists to take control of the relevant government bodies (they could acquire only “soft power” there, after all) and reject Indian culture as a particularly backward instance of false consciousness. For decades now, secularists have set the agenda and funded research projects and centres for “humiliation and exclusion studies.” Once the BJP comes to power, why not rewrite the textbooks and run educational bodies according to Hindutva tastes?

Second, there are examples of successful attempts at having books banned in the name of religion. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses is the cause célèbre. The relevant section of the Indian Penal Code crystallized in the context of early 20th-century controversies about texts that ridiculed the Prophet Muhammad. At the time, some jurists argued that non-Muslims could not be expected to endorse the special status given by Muslims to Muhammad as the messenger of God. That would indirectly force all citizens to accept Islam as true religion. Yet it was precisely there that Muslim litigants succeeded. If one group could use the law to indirectly compel all citizens to accept its claims concerning its holy book, religious doctrines and divine prophet, why not follow the same route?

Third, American scholars of religion came in handy for once. They had identified some questions they considered central to religious studies: What is the relation between insider and outsider perspectives? Who has the right to speak for a religion, the believer or the scholar? Originally, these were questions essential to a religion like Christianity, where accepting God’s revelation is the precondition of grasping its message. Yet the potential answers turned out to be useful to others: “Only Hindus should speak for Hinduism and scholarship can be allowed only in so far as it respects the believer’s perspective.”

What gives Hindu nationalists the capacity to conform so easily to these models? This is because they generally reproduce the Orientalist story about Hinduism, just adding another value judgement. They may believe they are fighting the secularists; in fact, they are also prisoners of what Balagangadhara has called “colonial consciousness.” That is, the Western discourse about India functions as the descriptive framework through which Hindu nationalists understand themselves and their culture. They also accept that this culture is constituted by a religion with its own sacred scriptures, gods, revelations, and doctrines. Within this framework, they can then easily mimic Islamic and Christian concerns about blasphemy and offence. Add the 19th-century Victorian prudishness adopted by the Indian middle class and you get prominent strands of the Doniger affair.

Consider the petition by Dinanath Batra and the Shiksha Bachao Andolan Samiti. Doniger’s suggestion that the Ramayana is a work of fiction written by human authors—a claim that would hardly create a stir in most Indians—is now transformed into a violation of the sacred scriptures of Hinduism. The petition claims that the cover of the book is offensive because “Lord Krishna is shown sitting on buttocks of a naked woman surrounded by other naked women” and that Doniger’s approach is that “of a woman hungry of sex.” It expresses shock at her claim that some Sanskrit texts reflect the “glorious sexual openness and insight” of the era in which they were written. To anyone familiar with the harm caused by Christian attitudes towards sex-as-sin, this would count as a reason to be proud of Indian culture. Yet the grips of Victorian morality have made these Hindus ashamed of a beautiful dimension of their traditions.

In the meantime, our middle-aged gentleman’s daughter has gone into the humanities and her excellent results give her entry to a PhD programme in religious studies at an Ivy League university. After some months, she begins to feel disappointed by the shallowness of the teaching and research. When compared to, say, the study of Buddhism, where a variety of perspectives flourish, Hinduism studies appears to be in a state of theoretical poverty. Refusing to take on the role of the native informant, she begins to voice her disagreement with her teachers. This is not appreciated and she soon learns that she has been branded “Hindutva.”

Around the same time, she detects a series of factual howlers and flawed translations in the works of eminent American scholars of Hinduism. When she points these out, several of her professors turn cold towards her. She is no longer invited to reading groups and is avoided at the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion. In response, this budding researcher begins to engage in self-censorship and looks for comfort among NRI families living nearby. Her dissertation, considered groundbreaking by some international colleagues, gets hardly any response from her supervisors. Looking for a job, the difficulties grow: she needs references from her professors but whom can she ask? She applies to some excellent universities but is never shortlisted. Confidentially, a senior colleague tells her that her reputation as a Hindutva sympathiser precedes her. Eventually, she gets a tenure-track position at some university in small-town Virginia, where she feels so isolated and miserable that she decides to return to India.

Intellectual freedom can be curbed in many ways. The current academic discourse on Indian culture is as dogmatic as its advocates are intolerant of alternative paradigms. They trivialize genuine critique by reducing this to some variety of “Hindu nationalism” or “romantic revivalism.” All too often ad hominem considerations (about the presumed ideological sympathies of an author) override cognitive assessment. Thus, alternative voices in the academic study of Indian culture are actively marginalized. This modus operandi constitutes one of the causes behind the growing hostility towards the doyens of Hinduism studies.

Again this strand surfaces in the Doniger affair. When critics pointed out factual blunders from the pages of The Hindus, this appears to have been happily ignored by Doniger and her publisher. She is known for her dismissal of all opposition to her work as tantrums of the Hindutva brigade. The debates on online forums like Kafila.org (a blog run by “progressive” South Asian intellectuals) smack of contempt for the “Hindu fanatics,” “fundamentalists” or “fascists” (read Arundathi Roy’s open letter to Penguin). More importantly, they show a refusal to examine the possibility that books by Doniger and other “eminent” scholars might be problematic because of purely cognitive reasons.

For instance, the petition charges Doniger with an agenda of Christian proselytizing hidden behind the “tales of sex and violence” she tells about Hinduism. This generates ridicule: Doniger is Jewish and she is a philologist not a missionary. Indeed, this point appears ludicrous and lacks credibility when put so crudely. As said, it also reflects the Victorian prudishness to which some social layers have succumbed. Yet, it pays off to try and understand this issue from a cognitive point of view.

A major problem of early Christianity in the Roman Empire was how to distinguish true Christians from pagan idolaters. Originally, martyrdom had been a helpful criterion but, once Christianity became dominant, the persecution ended and there were no more martyrs to be found. The distinction between true and false religion could not limit itself to specific religious acts. Those who followed the true God should also be demarcated from the followers of false gods by their everyday behaviour. Sex became a central criterion here. Christians were characterized in terms of chastity as opposed to pagan debauchery. (If you wish to see how this image of Greco-Roman paganism lives on in America, watch an episode of the television series Spartacus.)

From then on, Christians believed they could recognize false religion and its followers in terms of lewd sexual practices. Early travel reports sent from India to Europe, like those of the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema, confirmed this image of pagan idolatry: “Brahmin priests” and “superstitious believers” engaged in a variety of “obscene” practices from deflowering virgins in various ways to swapping wives for a night or two. Conversion to Christianity would entail conversion to chastity.

Reinforced by Victorian obsessions, this style of representing Indian religion reached its climax in the late 19th century. Hinduism was said to be the prime instance of “sex worship” and “phallicism,” notions popular at the time for explaining the origin of religion. Take a work by Hargrave Jennings—cleric, freemason, amateur of comparative religion—imaginatively titled Phallic Miscellanies; Facts and Phases of Ancient and Modern Sex Worship, As Illustrated Chiefly in the Religions of India (1891). The opening sentence goes thus: “India, beyond all countries on the face of the earth, is pre-eminently the home of the worship of the Phallus—the Linga puja; it has been so for ages and remains so still. This adoration is said to be one of the chief, if not the leading dogma of the Hindu religion….” It goes on to explain that “according to the Hindus, the Linga is God and God is the Linga; the fecundator, the generator, the creator in fact.” In other words, the Hindus view the phallus as their divine Creator and its worship is their dogma. This is one of a series of works from this period, expressing both fascination and disgust.

This focus on sex remained central to the popular image of Indian religion in the Western world. In her infamous Mother India (1927), the American Katherine Mayo writes that the Hindu infant that survives the birth-strain, “a feeble creature at best, bankrupt in bone-stuff and vitality, often venereally poisoned, always predisposed to any malady that may be afloat,” is raised by a mother guided by primitive superstitions. “Because of her place in the social system, child-bearing and matters of procreation are the woman’s one interest in life, her one subject of conversation, be her caste high or low. Therefore, the child growing up in the home learns, from earliest grasp of word and act, to dwell upon sex relations”. From there, Mayo turns to a reflection on the obsession for “the male generative organ” in Hindu religion. Among the consequences are child marriage and other immoral practices: “Little in the popular Hindu code suggests self-restraint in any direction, least of all in sex relations”.

In short, the connection established between Hinduism and sexuality was based in a Christian frame that served to distinguish pagan idolaters from true believers. Wendy Doniger’s work builds on this tradition. Like some of her predecessors, she appreciates the sexual freedom involved, but then she also tends to stress two aspects: sex and caste. This is not a coincidence, for these always counted as two major properties allowing Western audiences to appreciate the supposed inferiority of Hinduism. In other words, the sense that the current depiction of Indian traditions in terms of caste and sex is connected to earlier Christian critiques of false religion cannot be dismissed so easily.

Does this mean that researchers should give in to the campaigns of holier-than-thou bigots? Does it justify the banning or withdrawal of books? Not at all! First, who will decide what counts as true knowledge and what as salacious or gratuitous insult? In the US, evangelicals would like to remove Darwin’s Origin of Species from schools because they consider it unscientific and offensive. If it continues to follow its current route, the Indian judiciary may well end up banning a variety of such books. Second, book bans fail to have any fundamental effect on the kind of work produced about India. The epitome of the “sex and caste” genre, Arthur Miles’ The Land of the Lingam (1937), was banned many decades ago. Even though political correctness altered the language use and removed explicit mockery, many works continue to represent Hinduism along similar lines. Third, the Kama Sutra and the Koka Shastra, the temples of Khajuraho and Konarak, Tantric traditions and the Indian science of erotics are all fascinating phenomena, which need to be studied and understood. But we have an equal responsibility to make sense of the concerns of Indians horrified by the currently dominant depiction of their traditions. All this research should happen in complete freedom or it shall not happen at all.

The dispute about Doniger’s book is a product of all these forces, including the peculiarities of the Indian Penal Code (better left to legal experts). What is the way out? How can we untangle the knot?

To cope with complex cases like these, the first step should take the form of scientific research. The disagreement with the work of Doniger and other scholars can be expressed in a reasonable manner. The theoretical poverty and shoddy way of dealing with facts and translations exhibited by such works can be challenged on cognitive grounds. This is the only way to alleviate the frustration of our Hindu gentleman (a grandfather by now) and to illuminate the intellectual concerns of his daughter. In any case, we need to appreciate how the current story about Hinduism and caste continues to reproduce ideas derived from Christianity and its conceptual frameworks. As long as we keep selling the experience that one form of life (Western culture) has had of another (Indian culture) as God-given truth, the current conflict will not abate and our understanding of India will not progress.

But the same goes for using the Indian Penal Code to have books banned. Inevitably, this has chilling effects on the search for knowledge, at a time when India needs free research more than ever to save it from catastrophe. As is always the case, scientific research will bring about unexpected and unorthodox results. At any point, some or another group may feel offended by these, but this should never prevent us from continuing to pursue truth.

Unfortunately, the Indian government and judiciary have taken the route of succumbing to “offence” and “atrocity” claims by all kinds of communities. Given the political situation, this is unlikely to change any time soon. We can express moral outrage today. But tomorrow the challenge is to develop hypotheses that make sense of the current developments in India, including the violent rejection of the dominant representations of Indian culture. These need to show the way to new solutions so that an end may be brought to the banning and destruction of books in a culture that was always known for its intellectual freedom. –