This week school children everywhere will be dressing up as Pilgrims and Indians to reenact the first Thanksgiving. They’ll learn that the starving Pilgrims were saved by a group of Indians who generously donated barrels of corn and squash. That these two groups – despite speaking different languages and a long history of violence – looked past their differences to break bread together.

When I was in kindergarten, my parents refused to let me partake in these seemingly innocent holiday activities. For my father, who is a Pueblo Indian from the Ohkay Owigeh reservation, seeing his daughter weave plastic feathers into her hair and smile benevolently at the blondest students in class (who were always chosen to represent Pilgrims) was a gross misrepresentation of Native history and a perfect example of modern cultural appropriation.

It’s not that we don’t celebrate Thanksgiving – we do. Our family’s meal looks like any other family’s traditional feast. It’s just that my Mexican mother and Native American father know that the history surrounding that historical and isolated meal is bloody and sad, and that ethnic minorities, especially Native Americans, are still fighting an uphill battle for equal rights and accurate representation in United States history. No amount of free corn and squash is going to fix it.

For example, just last week – hundreds of years after the first Thanksgiving – a high school cheerleading squad in McCalla, Alabama decided to welcome a rival team during the state football playoff game with a large banner reading, “ Hey Indians, get ready to leave in a Trail of Tears Round 2.” The inappropriate sign quickly went viral among Native American groups who protested its gross insensitivity. Not only was the rival team named after a racial group, but the opposing cheerleaders chose to use a historical event where thousands of Natives were forced into exile and murdered as a representation for their high school football game.

How did this happen in the 21st century? If the cheerleaders had used the Holocaust or even slavery as an example, the media would’ve been up in arms over the blatant racism. But because the offense was directed towards Native Americans, it largely went unreported except by Natives themselves.

And this isn’t the only way that Natives are being misused as sports mascots. Controversy has surrounded the Washington Redskins for years over whether or not they should change their team name. The term “redskins” is a racial slur referencing Native skin color. I thought that in this day and age it was universally accepted that any term referencing a person’s skin color was always inappropriate and rude. Yet, Sunday after Sunday the Washington Redskins are introduced to adoring fans toting fake headdresses, ridiculous face paint, and other traditional and sacred Native symbols that have been turned into commodities for souvenir shops. The NFL would never allow a team to call themselves the New York Jews, or the San Francisco Chinamen. Why then is it so common to commodify Native Americans?

Those in defense of the Redskins name and those school administrators who saw no fault in the banner, might say that there are bigger issues to tackle regarding Native American affairs that extend beyond the gridiron. I agree – changing the name of a football team won’t change the rampant poverty and drug abuse on many reservations or the government policies and federal budget cuts that keep Natives ostracized. But it’s a start. It is often too easy to marginalize a people that make up less than 2 percent of the national population, and if nothing else, the Washington Redskins scandal is forcing families throughout the nation to talk about Native Americans not as historical figures but modern Americans who have played an important role in the history of this nation and deserved to be treated with respect.

It’s a difficult topic with a lot of history, but this week more than ever is time to reflect on the historical significance of Native Americans – from the first Thanksgiving to the occupation of Alcatraz – and how an entire race is openly being marginalized and commodified. After all, we could’ve just let those damn Pilgrims starve.

THANKSGIVING: A Day of Mourning

By Roy Cook

Most school children are taught that Native Americans helped the Pilgrims and were invited to the first Thanksgiving feast. Young children’s conceptions of Native Americans often develop out of media portrayals and classroom role playing of the events of the First Thanksgiving. The conception of Native Americans gained from such early exposure is both inaccurate and potentially damaging to others. Therefore, most children do not know the following facts, which explain why many American Indians today call Thanksgiving a “Day of Mourning”.

Traditional hospitality and generosity have and continue to be constant Tribal virtues to be practiced at all times.

One of a series of feasts reaching back into the group memory has been seized upon by the current modern society. The Wampanoag feast, called Nikkomosachmiawene, or Grand Sachem’s Council Feast. It was because of this feast in 1621 that the Wampanoags had amassed the food to help the Pilgrims thereby creating a new tradition European tradition known today as “Thanksgiving Day.” This Wampanog feast is marked by traditional food and games, telling of stories and legends, sacred ceremonies and councils on the affairs of the nation. Massasoit came with 90 Wampanog men and brought five deer, fish, all the food and Wampanog cooks.

Before the Pilgrims arrived Plymouth had been the site of a Pawtuxet village which was wiped out by a plague (introduced by English explorers looking to grab a piece of the New World land) five years before the Pilgrims landed These Native peoples had met Europeans before the Pilgrims arrived. One such European was Captain Thomas Hunt, who started trading with the Native people in 1614. He captued Native people onto ships and then imprisoned and enslaved them. These expeditions carried smallpox, typhus, measles and ored 20 Pawtuxcts and seven Naugassets, selling them as slaves in Spain. Many other European expeditions also lurther European diseases to this continent. Native people had no immunity and some groups were totally wiped out while others were severely decimated. An estimated 72,000 to 90,000 people lived in southern New England before contact with Europeans. One hundred years later, their numbers were reduced by 80%. It was the English Captain Thomas Hunt’s expedition that brought the plague, which destroyed the Pawtnxet. . The nearest other people were the Wampanoag. In modern times they are often simply known as the Indians who met the Pilgrim invasion, their lands stretched from present day Narragansett Bay to Cape Cod. Like most other Tribal peoples in the area, the Wampanoag were farmers and hunters.

Wampanoag is the collective name of the indigenous people of southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island. The name has been variously translated as “Eastern People”, “People of the Dawn”, or more currently “People of the First Light”. (Note 1)

The pilgrims (who did not even call themselves pilgrims) did not come here seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland. They came here as part of a commercial venture. One of the very first things they did when they arrived on Cape Cod — before they even made it to Plymouth — was to rob Wampanoag graves at Corn Hill and steal as much of the Indians’ winter provisions as they were able to carry. (Suppressed 1970 Speech of Wamsutta (Frank B.) James, Wampanoag.) To the native people who had observed these actions, it was a serious desecration and insult to their dead.

The angry Wampanoags attacked with a small group, but were frightened off with gunfire. When the Pilgrims had settled in and were working in the fields, they saw a group of Native people approaching. Running away to get their guns, the Pilgrims left their tools behind and the Native people took them. Not long after, in February of 1621, Samoset, a leader of the Wabnaki peoples, walked into the village saying “Welcome,” in English. Samoset was from Maine, where he had met English fishing boats and according to some accounts was taken prisoner to England, finally managing to return to the Plymouth area, six months before the Pilgrims arrived. Samoset told the Pilgrims about all the Native nations in the area and about the Wampanoag people and their leader. Massasoit. He also told of the experience of the Pawtuxet and Nauset people with Europeans. Samoset spoke about a friend of his called Tisquantum (Squanto), who also spoke English. Samoset left, promising the Pilgrims he would arrange for a return of their tools.

Samoset returned with 60 Native people including Massasoit and Tisquantum. Edward Winslow, a Pilgrim, went to present them with gifts and to make a speech saying that King James wished to make an alliance with Massasoit. (This was not true.) Massasoit signed a treaty, which was heavily slanted in favor of the Pilgrims. The treaty said that no Native person would harm a European settler or, should they do so, they would be surrendered to them for punishment. Wampanoags visiting the settlements were to go unarmed; the Wampanoags and the non-Indians agreed to help one another in case of attack; and Massasoit agreed to notify all the neighboring nations about the treaty.

The key figure in the treaty talks and in later encounters was Tisquantum. He was Pawtuxet who had been kidnapped and taken to England in 1605. He managed to return to New England, only to be captured by Captain Hunt and sold into slavery in Spain. He escaped and returning to this continent, on board ship he met Samoset. Tisquantum found that all of his people died of the plague, so he stayed with the Wampanoags, some of whom had survived the disease. Tiquantum remained with the Pilgrims for the rest of his life and was in large part responsible for their survival. The Pilgrims were not farmers nor woodsmen. They were city people and mainly artisans. Tisquantum taught them when and how to plant and fertilize corn and other crops. He taught them where the best fish were and how to catch them in traps, and many other survival skills. Governor Bradford called Tisquantum “a special instrument sent of God” The Native nations along the eastern seaboard practiced tribal spirituality, hospitality, and generosity.

Ironically, the first official “Day of Thanksgiving” was proclaimed in 1637 by Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop. He did so to celebrate the safe return of English colony men from Mystic, Connecticut. They massacred 600 Pequots that had laid down their weapons and accepted Christianity. They were rewarded with a vicious and cowardly slaughter by their new “brothers in Christ (Note 2)

Massasoit, who had done so much to help the Pilgrims, had a son named Metacomet. As time went on and more Europeans arrived and took more land, Metacomet or Prince Phillip as he came to known and other tribal people began to take notice of self-serving ethics of the Pilgrims. After Metacoms father, Massasoit, died in 1662, Metacom was crowned King Phillip of the Pokanoket by the Europeans. King Phillip formed an alliance to remove the European settlers from their homeland. In 1675, after a series of arrogant actions by the colonists, King Phillip led his Indian confederacy into a war meant to save the tribes from extinction. Metacom adopted a policy of increasing but subtle resistance towards the English. Rumors began to fly among the English that “Philip” agreed to help the English enemies the French in 1667.

A band of armed Native men were discovered by colonial rangers in 1671, which led to a demand that the guns be surrendered. After further angry confrontations, Metacom was forced to sign a new treaty which unacceptably demanded he fully subject his people to the English government. The old decayed dream of the peaceful coexistence between two equal and sovereign peoples had ended with the rejection of the Treaty of 1621. Although nothing happened for four more years, war broke out in June, 1675. The winter of 1675-76 proved a harsh one for the People, who resorted to raiding English farming communities for food and supplies. Many of the Christian Native People, especially those of Natick, Ponkapoag, and Mattakeeset were forced into internment camps on Deer Island in Boston Harbor and Clark’s Island in Plymouth Harbor, supposedly to prevent them from aiding and abetting the enemy. (Note 3)

The eventual use of Native soldiers proved to be the turning point for the English. Their Native allies showed them effective methods for locating enemies, traveling lightly through the country, and fighting in guerrilla fashion. Small parties of Native and English rangers, supporting the larger English armies, wore down Metacom’s allies’ resistance and also caused many bands to turn to the English side. One of the most famous of the mixed Native and English ranger companies was led by Captain Benjamin Church of Plymouth Colony. Benjamin Church, who was an effective soldier, knew that area well. He had been successful in convincing the Saconett Indians and others to leave the ranks of Philip’s supporters and ally themselves to him. Aided by these Indian colleagues, Church began to hunt Philip down.

Bravely changing tactics, Philip returned to Mount Hope, where he would meet his fate. In July 1676 Church captured Philip’s wife and son. Soon after, the despondent Philip shot one of his warriors. The man’s brother would lead Church to the sachem, and on 12 August 1676 Church and his forces attacked Philip’s encampment. Philip was shot and killed by an Indian named Alderman, and the corpse was drawn, quartered, and beheaded. Philip’s head was placed upon a pole at Plymouth, where it served as a grisly reminder of the war. (Note 4)

The current Wampanoag have not forgotten. Their population consists of several groups, sometimes called “tribes”, who base their membership upon closely maintained kinship ties to the aboriginal communities. Supposedly there are approximately 4,000 Wampanoag, some living in the traditional homeland, some living where their jobs and lifestyles have taken them. The two best known groups are those of Mashpee on Cape Cod and those of Gay Head (Aquinnah) on Martha’s Vineyard, which is the only Wampanoag group recognized by the federal government. Other Wampanoag trace their ancestries from Herring Pond (Bourne), Fresh Pond (Plymouth), Watuppa or Troy (Fall River), Pokanoket (Bristol and Warren, R.I.), Chappaquiddick Island, Christiantown or Takemmy (West Tisbury) and other places.

|

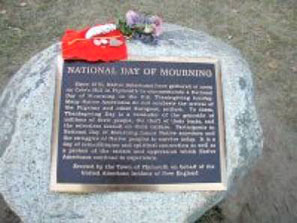

Text of Plaque on Cole’s Hill

“Since 1970, Native Americans have gathered at noon on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth to commemorate a National Day of Mourning on the US Thanksgiving holiday. Many Native Americans do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims and other European settlers. To them, Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their culture. Participants in a National Day of Mourning honor Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today. It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection as well as a protest of the racism and oppression which Native Americans continue to experience.”

Notes and Bibliography:

Note 1.

In this same time frame of English exploration, but much better known, is Capt. John Smith. He is the one who participated in the Powahatten area’s bounty. Although he would have much preferred to find gold. Capt. John Smith, has been immortalized for his part in founding Virginia. In 1614 Smith explored part of the North American coast-to which he gave the name New England. Disappointed in his search for gold, he set his men to fishing for cod while he went exploring in the ship’s pinnacle, mapping the coastline from Maine to the cape that was named for the fish.

Smith’s map and description of New England and his profits from cod fishing encouraged the Pilgrims to seek a charter from the Crown (The English Crown had no authority to grant legally.) to settle there. Indeed it was the cod that saved the first New Englanders. In 1640, only eleven years after Massachusetts Bay Company had been by the Puritans, it exported three hundred thousand cod to Europe. Cod was soon also being traded to the West Indies, in exchange for rum and molasses. In addition, plowing in the cod waste greatly increased the agricultural productivity of the stony New England soil. The cod proved a basis of prosperity for New England so considerable that Adam Smith singled it out for praise in his Wealth of Nations. To this day, a wooden sculpture of a cod adorns the Massachusetts Statehouse to remind the legislators of the source of their state’s greatness.

Note 2.

William Bradford, in his History of the Plymouth Plantation, described the carnage: “Those that scaped the fire were slaine with the sword; some hewed to peeces, others rune throw with their rapiers, so as they were quickly dispatche, and very few escaped. It was conceived they thus destroyed about 400 at this time. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fyer, and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stincke and sente there of, but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave the prayers thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to inclose their enemise in their hands, and gave them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enimie.” This is what Cotton Mather said, “It was supposed that no less than 600 souls were brought down to Hell that day”. At the same time he gives us an insight into the society and character of the Puritans. “…yet all this could not suppress the breaking out of sundry notorious sins.. Especially drunkenness and uncleanness. Not only incontinency between persons unmarried, for which many both men and women have been punished sharply enough, but some married persons also. But that which is worse, even sodomy and buggery (things fearful to name) have broke forth in this land oftener than once. I say it may justly be marveled at and cause us to fear and tremble at the considration of our corrupt natures, which are so hardly bridled, subdued and mortified…..But one reason may be that the Devil may carry a greater spite against the churches of Christ and the gospel here.”

Note 3.

In January, 1675 the body of a Christian Native named John Sassamon was found in the frozen pond at Assawompset (Middleboro). An alleged witness identified three Wampanoag men as the murderers of Sassamon. The three were arrested and tried by the General Court at Plymouth because the crime took place under English jurisdiction and the victim, being Christian, was considered an English subject. Rumor circulated that Metacom had commissioned the execution of Sassamon for revealing his plans.

In June, a colonist shot and mortally wounded a Pokanoket who had been seen running out of his house. A revenge raid followed in which several English were killed began the war. Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay and the Connecticut Colonies mustered their allied forces, and moved against Metacom. However, inept leadership allowed the Pokanoket to get away and raid many colonial towns. The Pokanoket, joined somewhat reluctantly by their Pocasset and Sakonnet relatives, retreated into the interior of Massachusetts where they were joined by some of the Nipmuck and others.

The war spread to the Connecticut valley and the Pokanoket went as far as the Hudson River to recruit allies amongst the Mahican, Abenaki, and others. The colonies, insisting that the Narragansett were acting in bad faith by harboring fugitives, prepared an army of 1,000 men to attack that neutral nation. In December 1675 the colonials attacked the unsuspecting Narragansett, burned their fort, and killed many of the inhabitants, thus driving the Narragansetts into the war on the side of Metacom.

Note 4.

King Philip’s War slowly came to an end after the sachem’s death. Some Indians were executed for their part in the fighting. Others, including Philip’s son, were sold into slavery abroad, even to Africa. The Wampanoag tribe was destroyed. Even Christian Indians who had backed the colonists suffered. Many colonists, angered by the heavy death toll of King Philip’s War, grew to hate all Indians, irrespective of their religion.

Much confusion has arisen over what name to use for Philip and the war. The sachem’s earlier name, Metacom, is preferred by some authors, but the sachem himself abandoned it. Indians commonly renamed themselves, and in 1674 he was calling himself Wewasowannett. Furthermore, the colonists were not ridiculing Philip when they referred to him by a European royal title. John Josselyn, who was sympathetic to the Indians, called the sachem “Prince Phillip” in his An Account of Two Voyages to New-England (1674). In addition, the term “King Philip’s War” acknowledges Philip’s great importance in the history of colonial New England. Therefore both King Philip and King Philip’s War are acceptable usages.

Metacom Education Project, Inc. P.O. Box 890082 East Weymouth, MA 02189, metedpro@netscape.net

Philip was illiterate, so there are only a few letters. See Massachusetts Historical Society, Collections, 1st ser., 2 (1793): 40, and 6 (1799): 94. Another letter is in Great Britain, Public Record Office, Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and the West Indies (1880), vol. for 1661-1668, p. 380.

The Records of the Colony of New Plymouth are essential. All contemporary accounts must be used cautiously, but see Benjamin Church, Entertaining Passages Relating to Philip’s War (1716); Increase Mather, A Brief History of the Warr with the Indians in New-England (1676); and William Hubbard, A Narrative of the Troubles with the Identity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998. Indians in New-England (1677). John Easton’s narrative is in Charles H. Lincoln, ed., Narratives of the Indian Wars, 1675-1699 (1913). The only modern scholarly biography is in Philip Ranlet, Enemies of the Bay Colony (1995).

His ancestry is given in Betty Groff Schroeder, “The True Lineage of King Philip (Sachem Metacom),” New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 144 (1990): 211-14. Alden T. Vaughan, New England Frontier, 3rd ed. (1995), is the best work for the years before the war. Douglas E. Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk (1958), is the most thorough military history of the war itself. Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America (1975), criticized Vaughan and Leach for being too favorable to the colonists.

Jennings, in turn, has been criticized by Philip Ranlet, “Another Look at the Causes of King Philip’s War,” New England Quarterly, 61 (1988): 79-100, and others for being too favorable to the Indians. Jill Lepore. The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American