“Swami Chinmayanda was an exemplary teacher – clear, convincing and with a lot of humour. On one of his Jnana Yajnas I took notes and wrote a long article for a German magazine. Later I gave its English translation to him. Swami Chinmayananda read through it and acknowledged that I had conveyed the teaching well, “but”, he added gravely and then broke into a smile “your English is very German.” – Maria Wirth

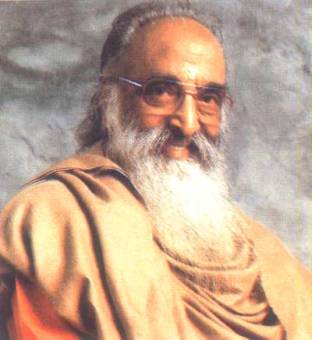

Swami Chinmayananda’s 100th birthday is on 8th May. He was born in Ernakulam in Kerala in 1916. Those who had the good fortune to meet the Swami in person, surely treasure his memory. He was a towering personality, who stood up for the Hindu tradition once he had realised its worth. He was a man on a mission – the mission to acquaint his countrymen, especially the English educated class, with the profound insights of the ancient Rishis, which were in danger of being forgotten. He started a revival of Hindu Dharma in independent India by translating the ancient knowledge into a modern idiom and teaching it all over the country and even abroad.

Swami Chinmayananda’s 100th birthday is on 8th May. He was born in Ernakulam in Kerala in 1916. Those who had the good fortune to meet the Swami in person, surely treasure his memory. He was a towering personality, who stood up for the Hindu tradition once he had realised its worth. He was a man on a mission – the mission to acquaint his countrymen, especially the English educated class, with the profound insights of the ancient Rishis, which were in danger of being forgotten. He started a revival of Hindu Dharma in independent India by translating the ancient knowledge into a modern idiom and teaching it all over the country and even abroad.

Swami Chinmayananda was the ideal person to do this, as he knew from own experience the mindset of the ‘modern’, English educated Indian who wrongly believes that he has no use for his heritage, mainly because he does not know it.

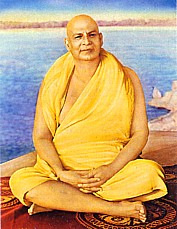

Balakrishna Menon, as he was called, was born into a pious household, but he himself was not inclined towards religion or spirituality. Nobody guessed that he would become a sannyasi. He was the proverbial left liberal youth, got involved in the freedom struggle and studied literature, law and journalism. His first job was with the National Herald newspaper. He wanted to make a story on the so called holy men in Rishikesh. In 1947, he reached Swami Sivananda’s ashram – not to learn from him, but to find out how these sadhus and swamis manage to bluff people. He planned to expose them.

However, things took a different turn. Obviously, Balakrishna Menon was greatly impressed by what transpired between Swami Sivananda and him, because two years later on Maha Shivaratri, he was back in Rishikesh and took sannyas. He became Swami Chinmayananda.

However, things took a different turn. Obviously, Balakrishna Menon was greatly impressed by what transpired between Swami Sivananda and him, because two years later on Maha Shivaratri, he was back in Rishikesh and took sannyas. He became Swami Chinmayananda.

From Rishikesh the new sannyasi went to Tapovan Maharaj in Uttarkashi deep in the Himalaya, and studied Vedanta as his disciple.

Discipleship, however, was not always easy, Once he even packed his bags determined to leave. His guru had accused him of having torn his cloth while washing it. Chinmayananda had denied it. Yet from that time onwards, Tapovan Maharaj called him ‘liar’, often in front of others. Chinmayanda felt hurt and decided to leave, never to come back. An older ashramite saw him packing and explained to him that the accusation was just one of the guru’s ways to hit at his ego, which was in his best interest. Chinmayananda got the point and stayed on.

When he saw his guru the next time, the guru laughed, “Why are you so touchy when I call you a liar? Aren’t we all liars as long as we don’t know the truth? Do you know the truth already?”

When he saw his guru the next time, the guru laughed, “Why are you so touchy when I call you a liar? Aren’t we all liars as long as we don’t know the truth? Do you know the truth already?”

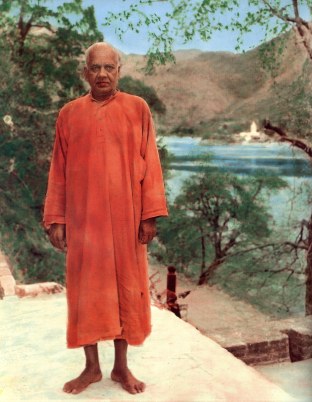

After several years with his teacher, Swami Chinmayananda felt the urge to share his insights into Vedanta – by now convinced that the happiness that all look for cannot be found where it is generally sought. Everyone searches outside in the world among other persons and things, while it is hidden deep inside.

In the early 1950s, he left the Himalayas for the dusty, hot plains and started teaching his fellow countrymen mainly about the Bhagavad-Gita and the Upanishads as even after Independence the education system inexplicably ignored those great Indian texts. The modern Indians had no idea that India once was the cradle of civilisation. Even the most popular of India’s sacred texts, the Bhagavad Gita, was hardly known anymore, nor the Upanishads which form the last part of the sacred Vedas and deal with profound philosophy.

Until his death in August 1993, Swami Chinmayananda hardly took off for a single day from his tight schedule. After reaching a town, that very same evening, he started his weeklong Jnana Yajna, as the camps were called. The Chinmaya Mission that he founded still exists, and trained Vedanta teachers still take classes all over the country.

I attended several of his camps, including a course in his retreat centre in Siddhabari and am grateful for that. Swami Chinmayanda was an exemplary teacher – clear, convincing and with a lot of humour. On one of his Jnana Yajnas (it was his 389th camp in 1983 in Trichy) I took notes and wrote a long article for a German magazine. Later I gave its English translation to him. Swami Chinmayananda read through it and acknowledged that I had conveyed the teaching well, “but”, he added gravely and then broke into a smile “your English is very German.”

Since my memory of that camp in Trichy is still fresh in my mind thanks to this article, I will give here a glimpse of it:

A big tent had been put up for the camp. Chants from the Bhagavad Gita were played in the background from stalls where cassettes and books were sold. About thousand people gathered at dusk, sitting on rugs on the floor.

When Swami Chinmayananda entered the stage, people welcomed him with heartfelt clapping. He looked stately, was tall, had long hair and a long white beard, sparkling and a little mischievous eyes and a roaring laughter. He was completely at ease and made us truly enjoy the class with his great sense of humour.

“Do you know the essence of Vedanta?” he asked in a booming voice and himself gave the answer, “The essence is: Undress and embrace” he thundered. People were nonplussed. He chuckled and explained, “Undress body, mind and intellect. What remains is automatically in intimate embrace with OM, the pure awareness.”

All our suffering stems from identifying with our body, mind and intellect, or in other words, with our thoughts and feelings, he claimed and gave an illustration: “You go and watch a movie. The persons on the screen experience happiness and suffering. You also experience happiness and suffering. Why? Because you identify with those figures. You sit in the theatre and cry into your handkerchief. And you even pay for it!”

It was easy to stay attentive for the two hours. He kept asking us not to believe him but to use our reason and common sense well, and analyse the human situation intelligently. For example ask yourself:

“Man has body, mind and intellect. If he has body, mind and intellect, who is he?” Certainly a good question! Usually a question that we have never asked ourselves. Amazing!

He gave the analogy of electricity: “If you believe only what you see, than each light bulb surely shines all by itself, since some shine brightly and others dimly and some red and some green. Does it not follow that each light bulb has its own, independent light?

Yet whoever inquires more deeply, will laugh at such ignorance. He knows that the one electricity is solely responsible for the light in all bulbs (and even for the sound from loudspeakers). The different colours and forms of the bulbs account for the variety in the lights, yet would there be any light without electricity? No!

Similarly, we should not take the sense perception that we all are ‘obviously’ separate at face value and enquire who we really are. What makes our body, mind and intelligence function? What mysterious power makes us feel alive as the subject, as “I”? Is it the same pure awareness which is responsible for the ‘light’ in all of us?” Yes, it is.

Swami Chinmayananda, too, like all sages, advised us to direct our attention inwards to that essence that alone is absolutely true. He advised to meditate on that mysterious OM and to develop love for it. He himself must have done it for innumerable hours in those long years in the Himalayan ashram of his guru. And he may have tapped into the source of all energy, love and joy which gave him the strength and enthusiasm to continue till the very end with his mission to make his countrymen see sense.

Swami Chinmayananda, too, like all sages, advised us to direct our attention inwards to that essence that alone is absolutely true. He advised to meditate on that mysterious OM and to develop love for it. He himself must have done it for innumerable hours in those long years in the Himalayan ashram of his guru. And he may have tapped into the source of all energy, love and joy which gave him the strength and enthusiasm to continue till the very end with his mission to make his countrymen see sense.

A bulb won’t be able to discover the electricity in itself, yet we humans can discover pure awareness, as we are already aware. We only need to drop the content of awareness to discover pure awareness which is our real and blissful nature.

The more we become aware of our real nature, the less we will be attached to the world. Desires will become less automatically. They simply drop off. The world does not bind anymore. Love and joy are not sought outside anymore. They are felt right here inside. Meditation and bhakti become natural.

Swami Chinmayananda gave again an example in his typical, humorous style, how a drastic change in attitude comes about naturally when the time is ripe:

“One day, the elder brother calls his younger brother, shows him all his toys and tells him, ‘it is all yours. If you don’t want it, throw it away.’ The younger one is convinced that unfortunately his elder brother has gone mad. Yet the elder one is not bothered. He has discovered a better toy, and knows that it is better. The little brother cannot see it as long as he is so small. One day he will understand….”

On the last evening, it became obvious that the Swami had done us a great service. Long queues formed, and slowly and silently moved in an almost sacred atmosphere to the carton boxes that had been put up near the dais for envelopes with donations. We were grateful for the many valuable insights that he had prompted us to have.

Now we only need to take them to heart. If we do, we can live life in a meaningful and fulfilling way – in tune with the eternal Dharma that flourished in India since ancient times. It is through people who live according to Dharma that it flourishes. –