The Hindu tradition emphasises Dharma and Rta; to live in harmony with cosmic order by being aware of one’s karma. It is ideas like this which the western mind cannot grasp, denouncing it as nebulous and illusory. One of the common criticisms is that Indian spiritual traditions denounce this world as Maya or illusion. But that is far too facile. For something so blessed with ‘illusion’ this longest unbroken surviving civilisation has many achievements to its credit. Indeed much of the modern world is a direct result of the Hindu mindset and such ‘nebulous’ ideas as moksha. Maya in fact does not mean illusion but our perception of reality and how it becomes distorted.

That does not impact one iota on the western ideologies which having become ‘secular’ and ‘rational’ and shedding all pretence at spirituality, become utterly materialistic in their core. All the while they retain their cultish and tribal nature as an exclusive club where only the initiates can fathom the deepest mysteries of the universe. This can be summed up in the 2005 gangster film, “Get Rich or Die Tryin” because stripped away from the veneer of modern sophistication, that is basically what it is, nature at its most brutal red in tooth and claw, but this time red in terms of mounting debt and a bleak future of subsistence on charity food handouts.

The Brand of Rand

Without a doubt the most far-reaching of the aforementioned ideologies of ultra-materialism has been Objectivism by Ayn Rand. Like so many others she defended individual liberty. However this was compromised in the real world by her major contribution to political, social and economic thought. She claimed to have invented the virtue of selfishness. More correctly she reflected how the American mentality was developing during the last century and from the 1950s her ideas resonated with a large section of baby boomer youth. Being selfish was no longer seen as something shameful.

Without a doubt the most far-reaching of the aforementioned ideologies of ultra-materialism has been Objectivism by Ayn Rand. Like so many others she defended individual liberty. However this was compromised in the real world by her major contribution to political, social and economic thought. She claimed to have invented the virtue of selfishness. More correctly she reflected how the American mentality was developing during the last century and from the 1950s her ideas resonated with a large section of baby boomer youth. Being selfish was no longer seen as something shameful.

It was creative, the very genius which led western civilisation and capitalism to become supreme, and America to be the most successful society to date. The skyscrapers of the New York skyline which so impressed a young Rand fresh from fleeing the Bolshevik regime and their murderous quashing of any attempt to independent endeavour and thought by subsuming the will of the individual under that good of the ‘collective’, led to Rand mitigating against social constraints. Long before Gordon Gecko bragged in Wall Street that “Greed is Good”, Rand was preaching that greed was ‘God’, inherently virtuous and necessary for the functioning of society. She boasted:

“My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.”

Further:

“there is only one fundamental alternative in the universe: existence or non-existence—and it pertains to a single class of entities: to living organisms. The existence of inanimate matter is unconditional, the existence of life is not: it depends on a specific course of action… It is only a living organism that faces a constant alternative: the issue of life or death…”

Altruism was out. Altruism was evil. Her novels laid out the sacred text for this imaginary world, where chisel-jawed Aryan types created wealth but had this stolen from them by ‘moochers’ a parasitic mass of government regulations, state officials and low intelligent majority who could not succeed in life. Rand styled herself on Aristotle, and claimed sacred chain with ancient Greek thought.

Altruism was out. Altruism was evil. Her novels laid out the sacred text for this imaginary world, where chisel-jawed Aryan types created wealth but had this stolen from them by ‘moochers’ a parasitic mass of government regulations, state officials and low intelligent majority who could not succeed in life. Rand styled herself on Aristotle, and claimed sacred chain with ancient Greek thought.

Atlas Shrugged was the unashamed glorification of the right of individuals to live entirely for their own interest. It inspired Alan Greenspan when he was 25 and like so many others helped form his intellectual defence of unfettered capitalism. Shortly after “Atlas Shrugged” was published in 1957, Mr. Greenspan wrote a letter to The New York Times to counter a critic’s comment that “the book was written out of hate.” Mr. Greenspan wrote:

“ ‘Atlas Shrugged’ is a celebration of life and happiness. Justice is unrelenting. Creative individuals and undeviating purpose and rationality achieve joy and fulfillment. Parasites who persistently avoid either purpose or reason perish as they should.”

And those deemed ‘parasites’ by Greenspan and his messiah Ayn Rand did indeed perish. Often by the million. Corporate eugenics and Social Darwinism really had no pity. As with Stalin and Mao the deaths of even millions was a statistic to be recorded and then filed away. There was plenty more human merchandise to exploit.

The Mystic Muck Contribution to Capitalism

Pretensions at individualism and ‘liberty’ however could not mask a major flaw. These skyscrapers could only have been built by accurate mathematical calculations and knowledge. That was only possible with a decimal number system and the use of ‘zero’. This is the major debt which western civilisation owes to the Hindu mindset and ancient India. Ayn Rand would have none of it because her metaphysics supported philosophical realism, and opposed anything she regarded as mysticism or supernaturalism, including all forms of religion. In the famous speech by John Gault in her last brainwashing text called “Atlas Shrugged” she has him denounce “the mystic muck of India”.

Pretensions at individualism and ‘liberty’ however could not mask a major flaw. These skyscrapers could only have been built by accurate mathematical calculations and knowledge. That was only possible with a decimal number system and the use of ‘zero’. This is the major debt which western civilisation owes to the Hindu mindset and ancient India. Ayn Rand would have none of it because her metaphysics supported philosophical realism, and opposed anything she regarded as mysticism or supernaturalism, including all forms of religion. In the famous speech by John Gault in her last brainwashing text called “Atlas Shrugged” she has him denounce “the mystic muck of India”.

Yet this mystic muck as she put it had helped shape the very capitalism she espoused. Rand preached that government was an interfering disease and that left without restrictions private enterprise would create prosperity for all. She had witnessed first-hand how communism had destroyed the social fabric of Russia and caused a brain drain.

Ayan Rand is popular among sections of the Anglophone middle-class youth in India who believe that Objectivism is the panacea to India’s state run crony capitalism known as Licence Raj, with its mind-boggling array of rules. But is it?

Modern capitalism and its ‘free’ market was anything but free at root. The prototype of the multinational was the British east India Company. Having won the right to collect tax under Mir Jafar of Bengal having defeated his enemies including the Mughal emperor at the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

Modern capitalism and its ‘free’ market was anything but free at root. The prototype of the multinational was the British east India Company. Having won the right to collect tax under Mir Jafar of Bengal having defeated his enemies including the Mughal emperor at the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

Long before Gordon Gecko and Ayn Rand the Company put the greed as virtue into practice. The Company’s money management practices came to be questioned, especially as it began to post net losses even as some Company servants, the “Nabobs,” returned to Britain with large fortunes, which—according to rumours then current—were acquired unscrupulously.

Raising taxes to enormous levels and forcing the population to plant indigo rather than food crops led to a massive famine in 1770. The famine is estimated to have caused the deaths of 10 million people. Horace Walpole wrote at the time: “We have murdered, deposed, plundered, usurped – nay, what think you of the famine in Bengal, in which millions perished, being caused by a monopoly of provisions by the servants of the East Indies.” However this was no natural disaster just due to monsoon failure as India was well equipped to dealing with this. What turned a manageable natural aberration into a human catastrophe was the manipulation of local grain markets by East India speculators, driving up the price of food beyond the reach of the masses.

Corporate as State

But as well as the human tragedy, here was a private enterprise which not just acted against the government but became the government. Yet one can scarcely imagine modern free market capitalism without the trailblazing of the East India Company.

But as well as the human tragedy, here was a private enterprise which not just acted against the government but became the government. Yet one can scarcely imagine modern free market capitalism without the trailblazing of the East India Company.

The onset of globalisation has revived interest in a company that could be seen as a pioneering force for world trade. Exhibitions at the British Library and the Victoria & Albert Museum as well as a string of popular histories, have sought to revive the reputation of the “Honourable East India Company”.

Its founders are now hailed as swashbuckling adventurers, its operations praised for pioneering the birth of modern consumerism and its glamorous executives profiled as multicultural “white moguls”. This romantic myth however is dashed when one looks at its more sinister lessons: abuse of market power; corporate greed; judicial impunity; the “irrational exuberance” of the financial markets; and the destruction of traditional economies. That godfather of liberal laissez-faire free market ideology himself was shocked.

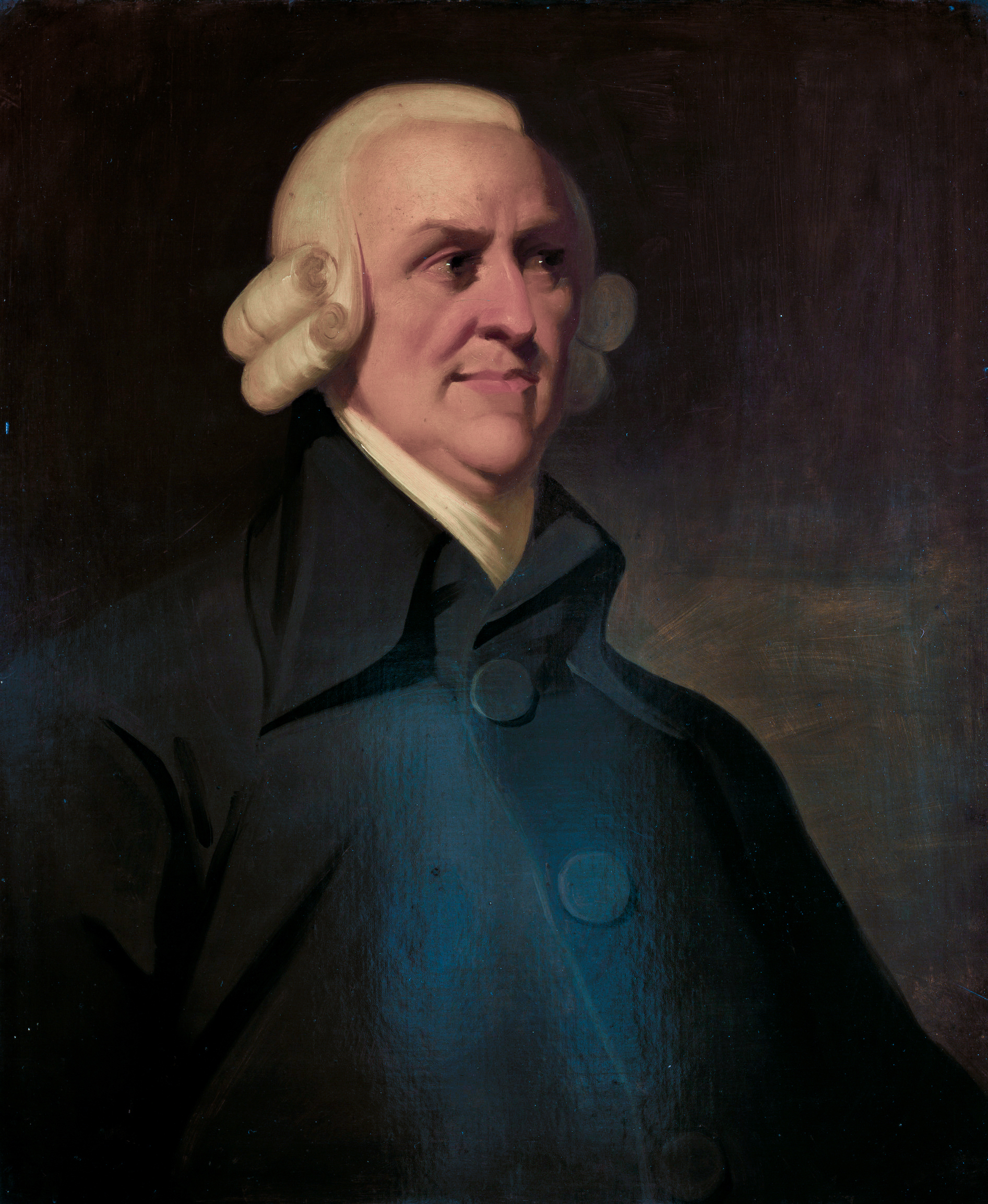

In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith used the East India Company as a case study to show how monopoly capitalism undermines both liberty and justice, and how the management of shareholder-controlled corporations invariably ends in “negligence, profusion and malversation”. Yet nothing of Smith’s scepticism of corporations, his criticism of their pursuit of monopoly and of their faulty system of governance, enters the speeches of today’s free-market advocates who claim to be the disciples of Smith. His vision of free trade entailed firm controls on corporate power, an anathema to deregulation, Thatcherism and above all Ayn Rand.

In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith used the East India Company as a case study to show how monopoly capitalism undermines both liberty and justice, and how the management of shareholder-controlled corporations invariably ends in “negligence, profusion and malversation”. Yet nothing of Smith’s scepticism of corporations, his criticism of their pursuit of monopoly and of their faulty system of governance, enters the speeches of today’s free-market advocates who claim to be the disciples of Smith. His vision of free trade entailed firm controls on corporate power, an anathema to deregulation, Thatcherism and above all Ayn Rand.

Internal and external checks and balances must curb the tendency of executives to become corporate emperors, with clear and enforceable systems of justice necessary to hold the corporation to account for any damage to society and the environment. These are tough conditions, and have rarely been met, either in the age of the East India Company or in today’s era of globalisation. Indeed Smith would ironically be denounced by his wayward offspring as a socialist or someone obsessed with state control on private enterprise.

But he was obsessed with good reason. After Robert Clive’s victory at the Battle of Palashi in 1757, the company literally looted Bengal’s treasury, loading the country’s gold and silver on to a fleet of more than a hundred boats and sent it downriver to Calcutta. In one stroke, Clive netted £2.5m (more than £200m today) for the company, and £234,000 (£20m) for himself. In what was not only the Company’s most successful business deal, but one which formed the foundation of the British Empire in India.

The Unfree Market

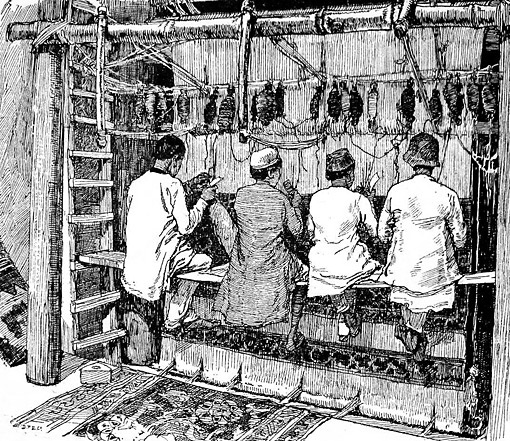

It would be Bengal’s weavers who felt the full force of the company’s new-found market power and the ‘free’ market. Though not exactly wealthy, these weavers nevertheless enjoyed a substantially better standard of living than their counterparts in 18th-century England. At a time when the British state was intervening on the side of the employer – for example, to set maximum levels for wages – India’s weavers were able to act collectively, aiding their ability to negotiate favourable prices. But the East India Company eliminated the weavers’ freedom to sell to other merchants, and so crushed their limited but important market autonomy.

It would be Bengal’s weavers who felt the full force of the company’s new-found market power and the ‘free’ market. Though not exactly wealthy, these weavers nevertheless enjoyed a substantially better standard of living than their counterparts in 18th-century England. At a time when the British state was intervening on the side of the employer – for example, to set maximum levels for wages – India’s weavers were able to act collectively, aiding their ability to negotiate favourable prices. But the East India Company eliminated the weavers’ freedom to sell to other merchants, and so crushed their limited but important market autonomy.

It imposed prices 40 per cent below the market rate, and enforced them with violence and imprisonment. Many weavers were driven to despair such as cutting off their own thumbs so that they could not be forced to work under these slave wages. But it was also the Company itself which organised thumbs to be amputated so that Bengali weavers would not compete with British textile imports. Ian Jack wrote in The Guardian on 20 June 2014 in his ominously entitled “Britain took more out of India than it put in – could China do the same to Britain?”:

“For at least two centuries the handloom weavers of Bengal produced some of the world’s most desirable fabrics, especially the fine muslins, light as “woven air”, that were in such demand for dressmaking and so cheap that Britain’s own cloth manufacturers conspired to cut off the fingers of Bengali weavers and break their looms. Their import was ended, however, by the imposition of duties and a flood of cheap fabric – cheaper even than poorly paid Bengali artisans could provide – from the new steam mills of northern England and lowland Scotland that conquered the Indian  as well the British market. India still grew cotton, but Bengal no longer spun or wove much of it. Weavers became beggars, while the population of Dhaka, which was once the great centre of muslin production, fell from several hundred thousand in 1760 to about 50,000 by the 1820s.”

as well the British market. India still grew cotton, but Bengal no longer spun or wove much of it. Weavers became beggars, while the population of Dhaka, which was once the great centre of muslin production, fell from several hundred thousand in 1760 to about 50,000 by the 1820s.”

Burgeoning free market and private enterprise thus actively de-industrialised India. Major cottage industries like textile, leather, oil, pottery were ruined and no alternative source of production was setup in India. Thus India had to depend on the British manufacturers. Exporter India was converted into an importer. Self-sufficient village economic gave way to colonial economy and India was transformed into an agricultural colony to produce and supply raw materials for the Company state.

All the parliamentary inquiries and waves of regulation, few of the company’s executives were ever brought to book. Clive narrowly escaped parliamentary censure in 1773, only to die by his own hand. Warren Hastings was protected from Parliamentary probing by Company shareholders and eventually was acquitted even when he was brought to trial.

Vitriolic in his case against Hastings, Edmund Burke argued for companies to be judged by their respect for what we would understand as universal human rights. The laws of morality,” he declared, “are the same everywhere . . . there is no action which would pass for an act of extortion, of peculation, of bribery, and oppression in England, that is not an act of extortion, of peculation, of bribery, and oppression in Europe, Asia, Africa and the world over.”

Vitriolic in his case against Hastings, Edmund Burke argued for companies to be judged by their respect for what we would understand as universal human rights. The laws of morality,” he declared, “are the same everywhere . . . there is no action which would pass for an act of extortion, of peculation, of bribery, and oppression in England, that is not an act of extortion, of peculation, of bribery, and oppression in Europe, Asia, Africa and the world over.”

When codes of conduct for company executives, rules on shareholder abuse, government regulation failed to tame the Company, it was eventually nationalised in 1857 when India became a possession of the Crown. India’s subsequent post-independence hostility to foreign investment was put down to the Fabian socialism of Nehru and the even more strident leftward drive under his daughter Indira Gandhi when India became a self-declared socialist republic. But this protectionist attitude had much to do with the experience India had of being taken over by a private trading company and becoming just another piece of corporate real estate.

Of course in being so protectionist and even xenephobic, the Gandhi-Nehrus merely brownwashed the faces of the Company Raj, retaining the old colonial structures which kept India de-industrialised and uncompetitive. The mental stranglehold was even stronger than the physical one of having weavers’ hands and thumbs chopped off by East India Company officials. Instead of Company Raj it was the kleptocratic rule of a neo-colonial elite which developed an almost pornographic fetish for paperwork, red tape and regulations: all of which could be sidestepped and ignored by greasing the right palms.

Chopping the Hands off British Manufacturing

In a karmic law of epic proportions, now Britain and America find themselves in the position India faced under the British East India company. Their governments beg for investment from the Chinese, and now the man they once scorned so openly, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India. After all Ian Jack began his article in the Guardian by stating:

In a karmic law of epic proportions, now Britain and America find themselves in the position India faced under the British East India company. Their governments beg for investment from the Chinese, and now the man they once scorned so openly, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India. After all Ian Jack began his article in the Guardian by stating:

“Large parts of India’s economy were destroyed by British technology in the 1800s, and by deals that favoured British shareholders. Today, it’s China that holds that kind of power.”

Further:

“It has taken 50 years of economic impotence and political wrong-headedness for the eventual consequence to emerge in the landscape: the rundown post-industrial settlements that have had their public funding cut, where town halls, shops, courts, police stations, post offices and local newspapers are closed or closing, stripping the place (as the Labour MP Jamie Reed wrote this week) of every symbol of permanence, community strength and civic identity, and forcing the more able individuals to up sticks and get out.”

And what did Jamie Reed warn about?

Manufacturing in the once mighty Anglophone nations have given way to service industries and automation, employing fewer people as millions end up on the dead end scrap heap of welfare dependency. However as jobs have become more scarce due to automation and outsourcing, the salaries of CEOs, directors and managers have skyrocketed to stratospheric levels.

The virtue of selfishness has become so pervasive that even charities pay their top executives six figure salaries, all the while sending gangs of agency staff to act like beggars and use emotional blackmail to elicit yet more millions from a public who have been neutralised of critical thinking. National debt is a burden to be carried by society’s most impoverished who have neither the voice nor lobbying power of corporate Caligulas to fight back. Human life has been stripped to its lowest unspiritual biological common denominator.

The reason we are being replaced by robots is because by and large we have become robots already. This was the dystopia Objectivism and similar monotheist ideologies did not reveal to the masses. In this nightmare world there is no individual liberty, merely the disconnect of atomised individual from those who wield power: state officials, corporate behemoths, trade union bosses.

The reason we are being replaced by robots is because by and large we have become robots already. This was the dystopia Objectivism and similar monotheist ideologies did not reveal to the masses. In this nightmare world there is no individual liberty, merely the disconnect of atomised individual from those who wield power: state officials, corporate behemoths, trade union bosses.

Under the onslaught of carbonated television diet and the crushing weight of state and the fixed market, humanity in rich nations resembles the shadowy dark underworld of Hades from ancient Greek mythology. But Rand was wrong. People do not act as individuals.

Even her cult became the very collective she preached against. In its stead arises the ‘tribe’, usually the gang. Give this gangster mentality a direction beyond just mere selfishness to get rich or die trying, and the flotsam element grows nastier and claims to be fighting for a higher ideal. Ethnic intolerance and the very modernist phenomena known as religious fundamentalism is the result.

Strip a people of their genuine spirituality and they will replace it with something that gives that amorphous ‘inner meaning’ because at its heart this free market capitalism and the virtue of selfishness it would spawn in Ayn Rand and Gordon Gecko is actually based on coercion and the crude curtailment of individual liberty. When private industry is allowed unfettered access to human raw materials, it does not just run in competition with the government, it becomes the government.

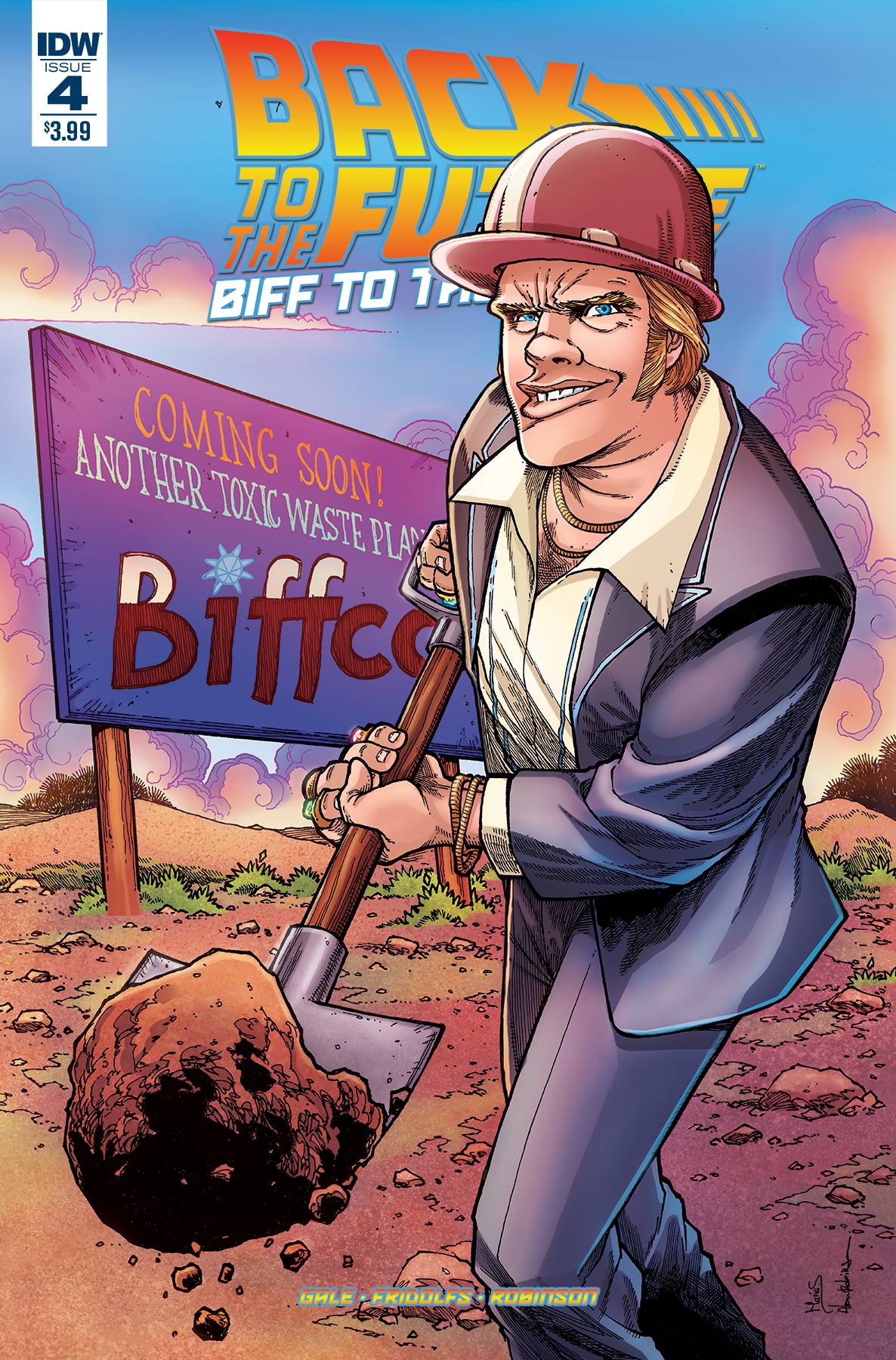

In Back to the Future II, Biff fat on the proceeds from an almanac of horse race records brought to him by his older self from an alternative future, is a private businessman who is above the law.

In Back to the Future II, Biff fat on the proceeds from an almanac of horse race records brought to him by his older self from an alternative future, is a private businessman who is above the law.

Hence his accurate bragging of “I own the police.” Is this so different from the British East India company having its own private army of sepoys? Of course in the real world, the Company used that private force to deadly effect taking over an entire subcontinent. The contemporary commentators at the time such as Adam Smith and Edmund Burke recognised this for what it was and did not try to excuse it. Even without this the free market is always compromised by the threat of monopolies and oligopolies which harm the masses and inhibit competition, entry and entrepreneurship because selfishness inevitably leads to such practices. It was just that the people of India under Company Raj during the Bengal Famine of 1770 and the weavers faced a joint force of state and corporate being one and the same. It would not be the last time.

Corporate Apartheid

The Royal Charter of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) came into effect on 20 December 1889 and expired in 1924. It was achieved through the efforts of politician and mining magnate Cecil Rhodes who as a boy had emigrated to South Africa from England. Achieving a monopoly over the Kimberley diamond mines which led to the creation of De Beers Consolidated Mines in 1888, helped Rhodes entrench his political power as Prime Minister of the Cape where he pushed for the disenfranchisement and pauperisation of Africans. In 1887 he said:

The Royal Charter of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) came into effect on 20 December 1889 and expired in 1924. It was achieved through the efforts of politician and mining magnate Cecil Rhodes who as a boy had emigrated to South Africa from England. Achieving a monopoly over the Kimberley diamond mines which led to the creation of De Beers Consolidated Mines in 1888, helped Rhodes entrench his political power as Prime Minister of the Cape where he pushed for the disenfranchisement and pauperisation of Africans. In 1887 he said:

“The native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise. We must adopt a system of despotism, such as works in India, in our relations with the barbarism of South Africa”.

The 1894 Glen Gray Act deprived the Xhosa people of their land and through labour tax compelled them to become cheap labour for white owned farms and industry. Rhodes raised the property and wealth threshold for being eligible to vote in order to deprive the majority of blacks and mixed race people the franchise.

Rhodes used his wealth and that of his business partner Alfred Beit and other investors to pursue his dream of creating a British Empire in new territories to the north by obtaining mineral concessions from the most powerful indigenous chiefs.

But Rhodes did not want the bureaucrats of the Colonial Office in London to interfere in the Empire in Africa. He wanted British settlers and local politicians and governors to run it. The charter gave BSAC the power to rule, police, and make new treaties and concessions from the Limpopo River to the great lakes of Central Africa.

Hence the formation of the British South Africa Police. The Company also assembled a Pioneer Column of 100 volunteers to occupy Matebeleland from King Lobengula.

The country was eventually named after Rhodes himself, and became Rhodesia. The new hut taxes concurrently compelled black peasants to find paid work, which could be found in the new agricultural industry, while also depriving the natives of the best land. The corporatocracy did not end until 1923 when Rhodesia became a self-governing territory of the empire under white minority rule. However Rhodes was not alone in his corporate colonialism.

From 1885 to 1908 King Leopold II of Belgium was the rule of the Congo Free State through a private company known as the International Association of the Congo. The official stockholders of the Committee for the Study of the Upper Congo were Dutch and British businessmen and a Belgian banker who was holding shares on behalf of Leopold.

From 1885 to 1908 King Leopold II of Belgium was the rule of the Congo Free State through a private company known as the International Association of the Congo. The official stockholders of the Committee for the Study of the Upper Congo were Dutch and British businessmen and a Belgian banker who was holding shares on behalf of Leopold.

The king pledged to suppress the East African slave trade; promote humanitarian policies; guarantee free trade within the colony; impose no import duties for twenty years; and encourage philanthropic and scientific enterprises.

In very short time he violated all of these. Leopold could not meet the costs of running the Congo Free State and hence put in brutal measures to increase productivity. Africans were required to provide State officials with set quotas of rubber and ivory at a fixed, government-mandated price and to provide food to the local post.

Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by death and Leopold’ police known as Force Publique collected amputated hands when the quotas could not be fulfilled. Rapes, massacres and depopulation became commonplace. From 1885 to 1908, it is estimated that the Congolese native population decreased by about ten million people. Due to international outcry Leopold’s private corporate fiefdom was ended and the Belgian state took over the running of the Congo.

28 Shopping Trips Later

In the past governments and states were formed by military conquest and similar force such as palace coups or successful peasant revolts. The eighteenth century saw how the pioneers of capitalism, far from reducing the power of the state, could actually become the state. In such reality the arguments for free trade, individual liberty or state interference become irrelevant. In 1887 Lord Acton put this vice trap situation so succinctly:

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority, still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority. There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it.”

In medieval Jewish folklore the golem is an animated anthropomorphic being, magically created entirely from inanimate matter. It is an automaton, created as the result of an intense, systematic, mystical meditation.

In medieval Jewish folklore the golem is an animated anthropomorphic being, magically created entirely from inanimate matter. It is an automaton, created as the result of an intense, systematic, mystical meditation.

The word golem means a body without a soul. Now golem possesses no spiritual qualities, because, quite simply, it does not have a human soul. It has been given the ruah, the “breath of bones”, or “animal soul”, the basic life force in all living things, but possesses nothing higher. It is typically not given a name. It is not considered a human being, nor does anyone in written accounts particularly concerned with its well-being or express any sadness at its deactivation.

The golem is simply an animated thing, like a robot, with no real life or desires of its own. It exists simply to the bidding of its master, a precursor to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Yet Shelley’s fictional monster was merely a nineteenth-century updating of not just the Golem but other deep horrors. Mechanical men and artificial beings appear in Greek myths, such as the golden robots of Hephaestus and Pygmalion’s Galatea. In the Middle Ages, there were rumours of secret mystical or alchemical means of placing mind into matter, such as Jābir ibn Hayyān’s Takwin, Paracelsus’ homunculus as well as Rabbi Judah Loew’s Golem.

One of the earliest descriptions of automata appears in the Lie Zi text in the third century BC, on a much earlier encounter between King Mu of Zhou (1023–957 BC) and a mechanical engineer known as Yan Shi, an ‘artificer’.

The latter allegedly presented the king with a life-size, human-shaped figure of his mechanical handiwork. With industrialisation these ideas no longer remained confined to an elite or avant-garde fringe.

In 1948, Norbert Wiener’s book, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, set off a scientific and technological revolution. But, alone among his peers, Wiener also saw the darker side of the new cybernetic era.

He foresaw the worldwide social, political, and economic upheavals that would begin to surface with the first large-scale applications of computers and automation. He saw a relentless momentum that would pit human beings against the seductive speed and efficiency of intelligent machines. He worried that the new time and labor-saving technology would prompt people to surrender to machines their own purpose, their powers of mind, and their most precious power of all—their capacity to choose.

He spoke passionately about rising threats to human values, freedoms, and spirituality that were still decades in the offing. His concerns formed the subject matter of his final popular work, God & Golem, Inc.: A Comment on Certain Points where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion. He wrote that as well as being able to absorb information and learn like humans, machines would also be able to replicate and reproduce themselves.

Wiener takes the image of the golem, which is a being made of clay and brought to life by a sorcerer, as a metaphor for the scientist who brings machines to life with cybernetics. Now in the present century fears exist that robots could make humans obsolete and swell the ranks of the unemployed and destitute. It is not just the factory workers at risk, as correctly predicted by Wiener.

Automation is predicted to replace the human face of journalism, commercial drivers, pharmacists, soldiers and astronauts. On 8 June 2014 Foxconn decided to tackle criticism of how it treated its workers by announcing that thousands of them would be replaced by robots to manufacture Iphones.

Automation is predicted to replace the human face of journalism, commercial drivers, pharmacists, soldiers and astronauts. On 8 June 2014 Foxconn decided to tackle criticism of how it treated its workers by announcing that thousands of them would be replaced by robots to manufacture Iphones.

But in many respects human beings, especially in industrialised countries, have in effect become robots or at least mindless automata like the medieval concept of the Golem. Science fiction offers us a revelation in the nightmarish world which already exists. In the film Logan’s Run the remnants of human civilization live in a sealed domed city, a utopia run by a computer that takes care of all aspects of their life, including reproduction.

The citizens live a hedonistic lifestyle but understand that in order to maintain the city, every resident when they reach the age of 30 must undergo the ritual of “Carrousel”. There, they are vaporized and ostensibly “Renewed.” In reality the mindless automata of today remain trapped mentally in permanent adolescence even while they bring the next generation into this world.

But in other respects the unspiritual dystopia of Logan’s Run has been accurate. But it is perhaps Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World which predicted most accurately the fluffy warm totalitarianism which dominates. In an omnipotent world state everyone’s needs are taken care of. Families are non-existent die to the process of laboratory child birth. Individuals are truly atomised before an all-powerful state.

All citizens are conditioned from birth to value consumption with such platitudes as “ending is better than mending,” “more stitches less riches” in order to feed the ever needed consumption to keep the economic system valid and relevant. Any need for transcendence, solitude and spiritual communion is addressed with the ubiquitous availability and universally endorsed consumption of the drug soma, a self-medicating comfort mechanism in the face of stress or discomfort, thereby eliminates the need for religion or other personal allegiances outside or beyond the World State. Marriage, natural birth, parenthood, and pregnancy are considered too obscene to be mentioned in casual conversation because this is a society where recreational sex is integral.

Solitude and deep-thinking are horrific ideas. With death there is no sorrow as family ties have simply evaporated. But surely this is a recommendation for Ayn Rand as she railed against the state. However this ignores that the extreme version of mindless consumerism could only be fuelled by such selfishness as virtue as preached by Objectivism.

It is even more obvious in the dystopian movie Robocop from 1987 and the sequels it spawned. Omni Consumer Products is a megacorporation which owns the privatised police department is a dystopian Detroit. OCP, throughout its depictions in the RoboCop films, has sought to fully privatize Detroit into “Delta City”, a manufactured municipality governed by a corporatocracy, with fully privatized services including the police, and with residents exercising their representative citizenship through the purchase of shares of OCP stock.

It is even more obvious in the dystopian movie Robocop from 1987 and the sequels it spawned. Omni Consumer Products is a megacorporation which owns the privatised police department is a dystopian Detroit. OCP, throughout its depictions in the RoboCop films, has sought to fully privatize Detroit into “Delta City”, a manufactured municipality governed by a corporatocracy, with fully privatized services including the police, and with residents exercising their representative citizenship through the purchase of shares of OCP stock.

They also serve as part of the military–industrial complex; according to OCP executive Richard “Dick” Jones, “We practically are the military.” Jones observes in RoboCop that OCP has “gambled in markets traditionally regarded as non-profit: hospitals, prisons, space exploration. I say good business is where you find it.”

By contrast the 2008 film Visioneers is a dark comedy of satire in which the Jeffers Corporation is the “largest, friendliest and most profitable business in the history of Mankind,” and is driving out a culture of independent thought and intimacy. The corporation and its leader, Mr. Jeffers, claim success is achieved by its strict philosophy of mindless productivity. Jeffers teaches that productivity equals happiness, and the business logo (a middle finger) is the standard greeting in society.

Two years earlier the dystopian comedy Idiocracy reveals a future where human intelligence has actually regressed.A single soft drinks company employs half the population of America, and uses its beverage to water crops causing massive food shortages. But attempts to rectify this cause the company’s share value to plummet and cause mass unemployment.

Two years earlier the dystopian comedy Idiocracy reveals a future where human intelligence has actually regressed.A single soft drinks company employs half the population of America, and uses its beverage to water crops causing massive food shortages. But attempts to rectify this cause the company’s share value to plummet and cause mass unemployment.

A darker theme is evident in the 1992 novel Snow Crash where the US federal government has ceded most of its power to private organizations and entrepreneurs. Franchising, individual sovereignty, and private vehicles reign, along with drug trafficking, violent crime, and traffic congestion.

Much of the territory ceded by the government has been carved up into sovereign enclaves, each run by its own big business franchise or the various residential burbclaves. Mercenary armies compete for national defence contracts while private security guards preserve the peace in sovereign, gated housing developments.

Highway companies compete to attract drivers to their roads and all mail delivery is by hired courier. The remnants of government maintain authority only in isolated compounds where they transact tedious make-work that is, by and large, irrelevant to the dynamic society around them. In his 2008 novel Jennifer Government, Max Barry described a trans-continental entity dominated by the USA, where government is privatised with the police reduced to a combination of law enforcement and mercenary agencies.

Most large corporations are now divided into two massive customer loyalty programs, US Alliance and Team Advantage, which fiercely compete with each other. US Alliance members include Nike, IBM, Pepsi, McDonald’s, and the NRA. Team Advantage members include the Police, ExxonMobil, Burger King, and Apple Computer. People even take the surnames of the corporations they work for, and a person with two jobs hyphenates their name (e.g. Julia Nike-McDonalds). Charity workers can also use their charity’s name in a hyphenated surname. Schools are now sponsored and controlled by corporations, such as McDonald’s and Mattel. There is pre-payment before emergency services can be dispatched, the abolition of welfare, the complete deregulation of weapons, legalised drugs sold in supermarkets and privately owned roads with toll charges.

The Hindu Victory Over Ultra-Materialism

What then is the solution, the antidote? Confucius famously put it:

“What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others.”

But it lies deeper. The sense of Dharma, Rta and understanding the effects of karma. Our actions have repercussions. Allowing the ego to run unchecked has devastating consequences not just for the individual but wider society. The Asuric and Devic (demonic and divine) attributes are in each of us. Ayn Rand taps into the former, celebrating it as the highest virtue. But there is a reason why Hindu tradition warned against this.

To look at the success or relevance of an idea we need to get beyond dogmatic confines and look at the effects. Rights without responsibilities are a sure route to dystopian nightmare. In Hindu tradition this debate is nothing new. In ancient India the materialist school of philosophy known as Charvaka was soundly defeated.

Ajita Kesakambali from the sixth century BC is the earliest known philosopher from this school. He preached a pure materialist doctrine in which altruism, good deeds and charity gained a man nothing in the end.

His body dissolved into the primary elements at death, no matter what he had or had not done. Nothing remained. Good and evil, charity and compassion were all irrelevant to a man’s fate. The basic tenets of Chārvāka philosophy, of no soul and existence of four (not five) elements, were probably inspired from him. But this school of thought was soundly defeated not by some evil scheme by powerful superstitious priests, but because it became irrelevant. If ever there was a free market it was this, the free market of ideas.

Rand’s cult together with fellow atheists and materialists may bemoan this. But without the Hindu mindset there would have been no zero and no decimal number system. Without this her hero Howard Roarke from Fountainhead could not have designed his modernist architecture because the Roman numerals which were in vogue before the Indian mathematical import would have simply been inadequate.

Rand’s hero owed his individualism to the very “mystic muck” which she would have John Gault decry in Atlas Shrugged. But then how could someone like Ayan Rand, who despite her rejection of religion and embrace of atheism, nevertheless continued in the same monotheistic paradigm in which she formed her Objectivist ideas?

Calling India “mystic muck” was the same swearology as calling everything else the “collective” even while she gathered useful idiot followers around her.

Calling India “mystic muck” was the same swearology as calling everything else the “collective” even while she gathered useful idiot followers around her.

This monotheist thinking does not need god as a deity, just an idea, and an idea against which it is blasphemous to even question. Change around the terminology and you might as well be speaking to a Marxist excusing the 100 million dead under communism as this true idea of scientific reasoning, rationalism and dialectic materialism not being implemented properly. The idea can never be wrong only the people who oppose it or are incapable of practising it properly.

What is needed is not an independent free mind but a mindless automata to carry out orders and follow ideas with blind obedience. That is why modern developed societies fear replacement by robots because apart from the flesh and blood that is what their inhabitants have become. Had this strand of thinking won in ancient India the very mathematical, scientific and abstract thinking which made the grimy industrial capitalist world of Ayn Rand possible would not even have existed. But the reason that Charvaka did not succeed was that it denied our very spiritual essence as irrelevant. It is clearly extremely relevant.