The following 4 part series of articles with a final conclusion article by Sandeep from The Rediscovery of India blog exposes the distortions and misinformation being spread by the Indian hindu hating collective. Please read and be armed with knowledge when facing such garbage which is being promoted in mainstream Indian media and academia presently.

The Rape of Our Epics: Part 1

Introduction

Nilanjana Roy’s Business Standard piece on Jan 08, 2013 entitled A woman alone in the forest is just the latest in what has become a much-lauded fad. A fad whose staple diet consists of a distorted reading of Indian epics, misinterpretations aplenty, sleights of hand, concealment, and open falsehood. We’ve seen the disastrous results of what happens when such untruths come to be accepted as truth—simply put, they multiply and over time gain such wide currency that even when the truth is pointed out, people simply dismiss it as propaganda or ranting or both. This problem is made worse in a country like India where the English media refuses to give voice to opposing and/or honest viewpoints.

Nilanjana Roy’s Business Standard piece on Jan 08, 2013 entitled A woman alone in the forest is just the latest in what has become a much-lauded fad. A fad whose staple diet consists of a distorted reading of Indian epics, misinterpretations aplenty, sleights of hand, concealment, and open falsehood. We’ve seen the disastrous results of what happens when such untruths come to be accepted as truth—simply put, they multiply and over time gain such wide currency that even when the truth is pointed out, people simply dismiss it as propaganda or ranting or both. This problem is made worse in a country like India where the English media refuses to give voice to opposing and/or honest viewpoints.

Nilanjana Roy’s piece tries to do two things at the same time: it tries to pin the blame for that Delhi lady’s brutal rape on our epics and like a corollary of sorts, tries to show that “if you hurt the wrong woman, prepare for war.” Among others, a key message of her piece is the fact that our epics have fashioned the way Indians regard and treat women, which includes condoning rape. read on

The Rape of Our Epics: Part 2

Is Draupadi Rarely Referenced?

After failing to show how Sita’s abduction by Ravana and her abandonment by Rama qualify as “rape” and/or “sexual assault,” Nilanjana Roy turns to Draupadi whom she characterizes as follows:

After failing to show how Sita’s abduction by Ravana and her abandonment by Rama qualify as “rape” and/or “sexual assault,” Nilanjana Roy turns to Draupadi whom she characterizes as follows:

Draupadi’s story is rarely referenced, though it is powerfully told in the Mahabharata. Draupadi’s reaction, after Krishna rescues her from Dushasana’s assault while her husbands and clan elders sit by in passive silence, is not meek gratitude. She berates the men for their complicity and their refusal to defend her; instead of the shame visited on women who have been sexually assaulted, she expresses a fierce, searing anger.read on

The Rape of Our Epics: Part 3

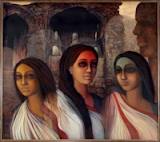

After trying to force-fit Draupadi into the feminist mould, Nilanjana Roy sets her sights on Amba, Ambika and Ambalika in yet another extremely revealing paragraph.

After trying to force-fit Draupadi into the feminist mould, Nilanjana Roy sets her sights on Amba, Ambika and Ambalika in yet another extremely revealing paragraph.

Amba is, again, silenced in popular discussion, and yet her story remains both remarkable and disquieting — the woman who will even become a man in order to wreak revenge on the man who first abducts and then rejects her. There is nothing easy about her story, as anyone who has tried to rewrite the Mahabharata knows; or about the way in which we gloss over the sanctioned rapes of Ambika and Ambalika, one so afraid of the man who is in her bed that she shuts her eyes so as not to see him.

How? And who has silenced Amba in “popular discussion?” Phrases like this are always intriguing simply because they hang loose. There are a gazillion things that fall under “popular discussion.” How does one define something like “popular discussion?” What constitutes a “popular discussion?” Films? Books? Music? Politics? Art? Mahabharata? What? But this is precisely where the beauty lies: building a narrative without defining something.read on

The Rape of Our Epics: Part 4

So where were we? Popular discussion? Niyoga? No…well, yes, we were at the three princesses: Amba, Ambika and Ambalika. Pardon my confusion. I mean, confusion happens when Nilanjana Roy mixes up timelines.

Imagine my plight: she begins with Sita, then moves to Draupadi. Correct: from Treta Yuga to Dwapara Yuga. Then she spends some time in Dwapara Yuga. Suddenly she reverts to Treta Yuga, she reverts to Shurpanakha. But does she stop there? No. Without warning, she drags in Hidimbi.

That leaves Surpanakha, the woman in the forest; like the rakshasi Hidimbi, she sees herself as a free agent.read on

The Rape of Our Epics: Conclusion

Of all the great epics of the world, only the Ramayana and the Mahabharata continue to influence and shape the lives, values, and beliefs of the Indian people. The two epics are perhaps the greatest forces that unite the Indian people culturally, spiritually, and socially. And this fact is unique only to India. There is almost no direct relation to the life and culture of the Greece and Italy of today to the epics produced by their respective countries. If we observe the so-called critiques of the Indian epics in the early days by the Left, the underlying strain was to deride and destroy their appeal because that was one of the significant ways in which they could realize their pet project of a Red World in India.read on Courtesy : The Rediscovery of India

Of all the great epics of the world, only the Ramayana and the Mahabharata continue to influence and shape the lives, values, and beliefs of the Indian people. The two epics are perhaps the greatest forces that unite the Indian people culturally, spiritually, and socially. And this fact is unique only to India. There is almost no direct relation to the life and culture of the Greece and Italy of today to the epics produced by their respective countries. If we observe the so-called critiques of the Indian epics in the early days by the Left, the underlying strain was to deride and destroy their appeal because that was one of the significant ways in which they could realize their pet project of a Red World in India.read on Courtesy : The Rediscovery of India